The Potential Role of Polyphenol Epigallocatechin 3-Gallate (EGCG) in Delaying Metabolic Profile in Mice Fed with High Fat Diet.

Dr. Yousef Assy

Journal Name: Global Journal of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine

Volume 1, Issue 7, February Pages: 1-32

Received: January, 29, 2026, Reviewed: February 1, 2026, Accepted: February 04, 2026, Published: February 05, 2026

Unified Citation Journals, Pathology 2026: https://doi.org/10.52402/Pathology224

Co-authors Name: Johnny Amer, Ahmad Salhab, Qaiss Ihsan Bashara, Afif Meike, Maithalon Sabbagh

- Yousef Assy, M.D., a graduate of Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Previously served as a Research Assistant at Tel Aviv University in the Faculty of Humanities, History and Philosophy of Science Institute. Currently at the Galilee Medical Center in Nahariya, Israel.

- Afif Meike: Afif Meike, a graduate of An-Najah National University. Galilee Medical Center in Nahariya, Israel.

- Maithalon Sabbagh: Maithalon Sabbagh, M.D., a graduate of An-Najah National University. Ziv Medical Center, Safed, Israel.

- Qaiss Ihsan Bashara: Qaiss Ihsan Bashara, M.D., a graduate of An-Najah National University. Beilinson Hospital Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel.

Abstract

Background and aims: Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) is the most abundant catechin in tea used in many dietary supplements and is a polyphenol under basic research for its potential to affect human health and disease. The research explores EGCG’s potential effects in modulating bile acids hemostasis, improve metabolic profiles, and prevent or reduce liver fibrosis and steatosis. Methods: An experimental interventional approach was performed utilizing 48 C57BL/6J mice leptin-deficient Ob/Ob male mice fed a high-fat diet (Ob/ObHFD; Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) mice model) following approval by the IRB committee at An-Najah National University. Mice were divided into four groups: Ob/Ob littermate with and without EGCG and Ob/ObHFD with and without EGCG treatments administered intraperitoneally. The study meticulously measured liver injury biochemical markers of ALT and AST, serum bile acid levels, insulin resistance (via HOMA-IR scores), fasting blood sugar (FBS), lipid profile of serum cholesterol and triglycerides, and conducted histopathological staining for liver examinations using Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Sirius Red for inflammation and fibrosis scoring, respectively. In addition, RT-PCR was conducted to quantitate liver αSMA, collagen I, and TGF-β expressions. Results: Data indicate that EGCG significantly ameliorated the lipid profile, reduced FBS, and improved insulin sensitivity in Ob/ObHFD mice, suggesting a partial reversal of metabolic disturbances induced by a high-fat diet. Furthermore, EGCG treatment led to significant reductions in liver enzymes ALT and AST, indicative of reduced liver damage. Histopathological analysis confirmed the reduction in steatosis and fibrosis in the liver tissues of EGCG-treated mice, highlighting its protective effects against diet-induced liver damage. Pro-fibrogenic markers of liver αSMA, collagen I, and TGF-β expressions were significantly reduced following EGCG treatment (P<0.04). Conclusion: The study underscores EGCG’s therapeutic potential in mitigating metabolic syndrome and liver fibrosis associated with NASH. It suggests that EGCG can be a valuable natural compound for improving metabolic health and preventing liver-related complications in conditions characterized by obesity and insulin resistance. However, it also acknowledges the need for further research to understand the mechanisms underlying these benefits, determine optimal dosages, and confirm these findings in human clinical trials.

Keywords: EGCG: Epigallocatechin Gallate, NAFLD: Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance, ALT: Alanine Transaminase, AST: Aspartate Transaminase.

Dedication

First, we dedicated this effort to our families, loved ones ,and closest acquaintances, whose unwavering support and inspiration have served a significant role in our success, our determination to pursue knowledge, and our pursuit of the highest standards of performance. Our academic success rests on their faith, sacrifices, and ongoing drive, and we wouldn’t have gotten where we are now without them.

Second, we dedicate it to our doctors and supervisors, who we are extremely fond of the guidance expertise, and mentorship provided by them during this research work. Their essential tips and wisdom were integral in establishing a solid thesis that we are proud of.

Third, we dedicate it to our peers whose would like to express our gratitude to each of them for their support and hard work throughout our path in medical school. It has been the most difficult and demanding phase of our lives, but it has also been the most gratifying.

Fourth, we dedicate it to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at An-Najah National University.

Introduction

Herbal supplements and functional foods are popular for their nutritional and health benefits. Green tea is one of the most consumed beverages globally. (1,2) It contains polyphenols, caffeine, minerals, and traces of other compounds, with catechins being the main polyphenols.

(3) Green tea has various health effects, mainly due to epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), its principal bioactive constituent. EGCG has been investigated for its chemoprotective role, as it modulates cellular proliferation and apoptosis through inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases and downstream signaling pathways of cancer cells. (4,5) Studies have shown the positive impact of green tea on diseases such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, neurological disorders, inflammatory conditions, and cancer. The tea’s high antioxidant content improves the tissue’s redox state and prevents structural damage. (6–8) Green tea also prevents neural damage and neurodegenerative diseases. (9,11) Flavonoids, including EGCG, may have cardioprotective and metabolic effects by affecting endothelial function and blood pressure. (10) EGCG also displays anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines and eliminating free radicals. EGCG helps restore glutathione peroxidase activity and glutathione levels. (11,12) These results highlight EGCG’s potential as a useful natural compound with health-promoting effects.

Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) is a fatty liver disease caused by obesity and metabolic syndrome, which can lead to serious complications. It involves excess fat and inflammation in

the liver. Bile Acids (BA’s) are cholesterol-derived molecules that regulate cholesterol and lipid metabolism. They are reabsorbed by the liver through sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP), a major BA transporter. NTCP deficiency causes high BA levels in the blood, which can damage and inflame the liver. Obese patients with NASH have impaired NTCP function and high BA levels in the liver and blood. BAs and NTCP play a role in liver health. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of NASH may offer new insights and treatments for this common and severe liver disease. (13-15)

Salhab et al. suggested a relationship between high levels of BAs and the onset of NASH mediated by NTCP. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) covers a range of liver conditions, from simple steatosis to NASH, which markedly increases the risk of progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and other extra-hepatic complications. Remarkably, treatment with EGCG showed a significant reduction in genes related to liver fibrosis. Nevertheless, it is important to mention that there was an attempt to trigger NTCP endocytosis using EGCG as well. (13,17,18)

EGCG’s effects on liver steatosis and fibrosis are poorly understood, and there is insufficient scientific evidence to support green tea’s ability to improve metabolic profiles and insulin resistance or to treat liver injuries such as NASH, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Therefore, our study aims to address these knowledge gaps by examining whether EGCG can modulate bile acid trafficking and prevent the development of metabolic syndrome and NAFLD.

To achieve this, we will evaluate EGCG’s potential benefits on the metabolic profile of C57BL/6J male leptin deficient mice (Ob/Ob) fed on high fat diet that simulates the human Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) condition characterized by obesity and insulin resistance. We will then carefully assess the impact of EGCG on histopathological and clinical metabolic outcomes by measuring key parameters such as glucose, insulin, cholesterol, and triglyceride serum levels. Histologic analysis of liver samples will be conducted to identify microscopic changes, such as hepatocyte ballooning, regenerative nodules, and fibrous connective tissue bridging, which will enhance our understanding of the effects of EGCG. Through this thorough investigation, we aim to determine whether EGCG can reduce or delay the onset of metabolic syndrome and its related complications in the liver.

Methodology

Study design and setting

An experimental interventional study was conducted at An-Najah National University’s laboratories and pathology department. The study focused on male C57BL/6J mice, which have not previously been exposed to a high-fat diet. The mice (both Wild Type and Ob/Ob) aged 12 weeks, were cared for following An-Najah University’s ethical regulations and NIH guidelines, with the approval of the institutional animal care ethical committee.

During the study, the C57BL/6J – littermate and Ob/Ob mice- were housed in a barrier facility separately.

Ob/Ob mice fed a high-fat diet- Ob/Ob HFD– (HFD, Cat. # TD.06414 [60% Fat]; 18.3% Kcal protein, 21.4% Kcal carbohydrate, and 60.3% Kcal fat) for a duration of twelve weeks. At week four of the HFD, the mice were intraperitoneally treated with EGCG at a concentration of 100 g/Kgm/mice, twice a week, for an additional ten weeks.

Study population, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

For this experiment, 48 male C57BL/6J mice of the Naïve Black strain (24 littermates, 24 Ob/Ob HFD) were utilized; and subsequently divided into four groups based on the following criteria:

- Group 1: Naïve animals(littermate) on a normal diet without treatment (Control group).

- Group 2: Naïve animals(littermate) on normal diet treated with EGCG (Sigma, Cat# 50299-1MG-F; 100g/Kgm/mice) intraperitoneal injection twice a week for ten weeks

- Group 3: Ob/Ob HFD animal not treated with

- Group 4: Ob/Ob HFD animal treated with EGCG (Sigma, Cat# 50299-1MG-F; 100g/Kgm/mice) intraperitoneal injection twice a week, four weeks following HFD

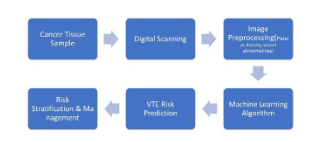

Flow chart describing and illustrating the course of the experiment:

Inclusion criteria

- Genotype: Both WT (Wild Type-Littermate-) and Ob/Ob mice will be included in the study, with their respective genotypes verified by genotyping.

- Age: Male mice aged 12 weeks at the start of the

- Body Weight: WT mice should have an average baseline body weight of 25-30

Ob/Ob mice should have an average baseline body weight of 45-50 grams.

- Health Status: All WT and Ob/Ob mice must be free of infectious diseases, and their health will be confirmed through a veterinarian examination prior to the experiment.

- Diet and Housing: All mice will be housed in a controlled environment with a standard laboratory diet and ad libitum access to water. The diet composition will be well-

Exclusion criteria

- Abnormal Behavior: Exclude mice that display severe abnormal behavior, as this may interfere with data collection.

- Weight Outliers: If the study requires a specific range of baseline weights, exclude mice with weights significantly outside of the specified range.

- Dietary Noncompliance: Exclude mice that refuse to consume the provided diet or water, as they may not be representative of the study population.

- Infections or Diseases: Exclude mice that develop infectious diseases or health issues during the experiment, as these conditions can confound the results.

- Injuries: Exclude mice that experience significant injuries, such as trauma, that could affect their ability to respond to the treatment.

Sample size and sampling techniques

This study aimed to investigate the effects of EGCG on obesity, metabolic disorders, liver injury, and fibrosis in mice. To fulfill this, we used 48 mice that were assigned to four groups of 12 mice each. All the experiments took place during the daytime to avoid disrupting the mice’s circadian rhythms.

- We measured the weight and collected blood samples from all the mice at the start of the study -to establish a baseline of our results- and every four weeks Then, we divided the mice into two main groups based on their genetic background: 1) Naïve mice (littermates) fed with a normal diet, and 2) Ob/Ob fed with a high-fat diet, for four weeks to induce different levels of metabolic stress.

- After the feeding period, each group was subdivided into further two groups (reaching a total of four groups) in which the administration of an intraperitoneal injection of EGCG was started in half of the mice in each main We then compared the

changes in weight, blood glucose, insulin, and other biomarkers among the four subgroups to determine the potential benefits of EGCG.

- Blood samples consisted of, CBC, lipid profile, insulin level, ALT, and AST. By analyzing these blood parameters, we’ve gained valuable insights into the physiological and metabolic changes occurring in the mice throughout the study, especially in response to different diets and EGCG treatments.

- The bile acid ELISA kit was employed to measure the levels of bile acids in

- After blood sampling, the HOMA-IR score was calculated using the fasting insulin and glucose measurements to assess insulin resistance in these animal models which mimics obese human patients with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

It shall provide valuable information about insulin resistance, which is crucial for understanding metabolic changes and responses to different diets, as well as the effects of EGCG on the metabolic profile based on blood sample analysis.

The formula for calculating the HOMA-IR score is as follows:

HOMA-IR = (Fasting Insulin (µU/L) * Fasting Glucose (mmol/L)) / 22.5.

- The blood samples were taken from the tails and cheeks, except the final sample it was collected from the heart directly at the end of the 12th week of the experiment through the process of scarifying the mice.

- Two days after the final EGCG injections, the mice were Before sacrifice, the mice were weighed, and then they were anesthetized intramuscularly using a mixture of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine at a ratio of 4:1:1 per 30 g of body weight. Following anesthesia, cervical dislocation will be performed to ensure euthanasia.

- Histologic examination was conducted at the end of week 12 during scarifying, sections from the liver were examined by using H&E stain and Sirius Red staining.

Operational definition:

Independent Variable

Genotype: Mice type used in the experiment, in this case, it’s a categorical variable with two levels, Wild-type and Ob/Ob mice.

Dependent Variables

Various biological, physiological, and pathological measures related to NASH can be considered dependent variables. These could include:

- Liver Function Markers: Such as levels of liver enzymes (e.g., ALT, AST).

- Histological Features: Histological assessments of liver tissue, including measures of steatosis (fat accumulation), inflammation, fibrosis, and hepatocellular ballooning.

- Serum Lipid Profiles: Cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the

- Inflammatory Markers: Cytokines, fibrosis markers or other markers of

- Metabolic Parameters: Measures of glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and body

Study tool, validity, and reliability

- Kits were used in this experiment are:

- Liver injury enzymes (ALT, AST) ELISA

- Glucose ELISA

- Bile acids ELISA

- RNA isolation

- cDNA isolation

- Stains were assessed in histopathological examination of liver specimens:

- H&E

- Sirius Red

Histological assessments of mice livers

The posterior one-third of the liver was fixed with 4% formalin for 24 hours at room temperature and was then embedded in paraffin in an automated tissue processor. Sections (7 mm) were deparaffinized by immersing them in xylene. Sections were then rehydrated by passing them through a series of graded alcohols, starting with absolute alcohol and ending with distilled water. H&E staining is used to evaluate steatosis, necro inflammatory regions, and apoptotic bodies, in addition, livers were stained with 0.1% Sirius red F3B in saturated picric acid (ab150681, abcam) to visualize connective tissue and fibrosis. Veterinary pathologist assessed all histopathological findings and reported assessments grading. For fibrosis area quantification, stained slides were scanned using a Zeiss microscope equipped with image analysis software (ImageJ) to outline the fibrotic areas within the tissue section .The fibrosis area was calculated by dividing the total fibrosis area by the number of fields of view or sections analysed.

Serum biochemical assessment

Following mice fasting for 16 hours, mice whole blood samples were collected from the heart on the sacrificing day and were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. Serum ALT (Abcam; ab285263), AST (Abcam; ab263882), cholesterol (Abcam; ab285242), triglyceride (Abcam; ab65336), fast blood sugar (Glucose) (Abcam; ab65333), insulin (Abcam; ab277390), and total BAs (Abcam; ab239702) were performed using ELISA kits according to the manufacture protocols. Briefly, all reagents and samples were brought to room temperature (18

– 25 °C) before use. A volume of 100 µL of each standard and sample was added into appropriate wells and incubated for 2.5 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking. The solution was discarded, and wells were washed 4 times with 1X Wash Solution, of note; washing was done by filling each well with Wash Buffer (300 µL) using a multi-channel Pipette or auto washer. Following the washing, the liquid was completely removed at each step which is essential to have good performance. A volume of 100 µL of 1x prepared detection antibody was added to each well for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle shaking. A volume of 100 µL of prepared streptavidin solution was added to each well for 45 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking. A volume of 100 µL of TMB One-Step Substrate Reagent (Item H) was added to each well for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark with gentle shaking. Finally,

50 µL of Stop Solution (Item I) was added to each well. Absorbance was read at 450 nm immediately using an ELISA reader (Tecan M100 Plate Reader).

RT-PCR kits, which include RNA and cDNA isolation kits

played a crucial role in evaluating fibrotic marker gene expression for several key reasons. Fibrosis, a complex process involving the excessive buildup of extracellular matrix components, requires a specific focus on gene expressions. Isolating mRNA from the target tissue (liver) or cells enabled us to precisely examine the genes associated with fibrosis, providing a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved. mRNA serves as an intermediary between genes and proteins, making it a valuable indicator of gene activity. Converting mRNA to cDNA through reverse transcription enhances its stability and facilitates efficient analysis using techniques like quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). This quantitative approach allowed us to accurately measure the expression levels of fibrotic marker genes, offering valuable insights into disease progression, potential therapeutic targets, and the effectiveness of treatments aimed at mitigating fibrosis. In our experiment, total cellular RNA was isolated from liver tissue with 2 ml TRI Reagent (Bio Lab; Cat# 90102331) per cm3 of tissue. The samples were homogenized for 5 minutes at room temperature, and 0.2 ml chloroform (Bio Lab; Cat# 03080521) was added. The samples were then incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature and centrifuged (1,400 rpm) for 15 minutes at 4°C. For RNA precipitation, the supernatant in each sample was transferred to a new micro- centrifuge tube, and 0.5 ml of isopropanol (Bio Lab; Cat# 16260521) was added, followed by 10 minutes incubation at 25°C. The tubes were then centrifuged (12,000 rpm) for 10 minutes at 4°C, the supernatants were removed, and one ml of 75% ethanol was added to the pellet, followed by centrifugation (7,500 rpm) for 5 minutes. The pellets were air-dried at room temperature for 15 minutes, 50 μl of DEPC was added, and the samples were heated for ten minutes at 55°C. RNA purification from the liver was assessed using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (CAT# 74034) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Preparation of cDNA was performed with a High-Capacity cDNA Isolation Kit (R&D; Cat# 1406197). Real-time PCR was performed with TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Cat# 4371130) to quantify αSMA, collagen I, and TGF-β expressions, data were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH and analyzed using QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System.

Bile acids ELISA kit

The bile acids ELISA kit played a crucial role in accurately assessing the levels of total bile acids present in the serum of the different groups of mice. The ELISA’s specificity is conferred by antibodies that selectively bind bile acids, facilitating the detection and quantification of these compounds with notable sensitivity and precision. In the assessment of serum bile acid concentrations utilizing a bile acid ELISA kit, the assay follows a competitive binding protocol. Initially, serum samples, alongside predetermined standards, and controls, are prepared as per the kit’s instructions, which may include specific dilution protocols. The ELISA plate wells come pre-coated with antibodies specific to bile acids. During the assay, these antibodies engage in competitive binding with both the bile acids in the samples and an added enzyme- labeled bile acid. Following a precise incubation period, which facilitates the binding interactions, the wells are thoroughly washed to remove unbound components. A substrate is then introduced to the wells, reacting with the enzyme-labeled bile acid to produce a measurable color change. The reaction is ceased at a defined time with a stop solution to prevent overdevelopment. The resulting color intensity is inversely related to the bile acid concentration in the samples; this is quantified using a spectrophotometer. The optical densities obtained are then plotted against the standard curve to ascertain the bile acid concentrations of the samples, ensuring accurate and standardized measurement of bile acid levels as dictated by the kit’s stringent protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (for comparison between two groups) or a one-way and two-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post-tests for multiple groups) with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data are represented as mean±SEM.

Ethical Approval

The study followed the regulations and ethics of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at An- Najah National University. All collected data was saved in a secret manner that allowed just the principal investigators and the study analyst to evaluate and conduct the proper statistical analysis. After this study was finished, the data was saved by the principal investigators in a proper way that may benefit any future similar or related studies.

Results

Biochemical profile assessments in the Ob/ObHFD -induced liver damage mice model- and Littermate mice-control group – following treatment with EGCG.

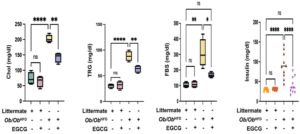

The graphs compare the effects of EGCG on the cholesterol (Chol), triglycerides (TRG), fasting blood sugar (FBS) and insulin levels of four groups of mice: littermates on normal diet with or without EGCG, and Ob/Ob HFD animals with or without EGCG.

Ob/Ob HFD showed an increased serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, FBS and insulin with metabolic profile perturbation; therefore, we adopted this model to characterize metabolic outcomes of these markers following treatments with EGCG.

The Cholesterol (Chol) graph shows (Figure 1): that EGCG treatment had no significant effect on cholesterol levels in littermates on a normal diet, which had the lowest mean of 60 mg/dl. Ob/Ob HFD mice without EGCG had the highest mean of 200 mg/dl, reflecting their dyslipidaemia and increased cardiovascular risk. EGCG treatment significantly reduced cholesterol levels in Ob/Ob HFD mice, but they remained higher than in littermates, with a mean of 150 mg/dl. This indicates that EGCG may improve cholesterol metabolism in Ob/Ob HFD mice, but it is not enough to normalize their levels.

The Triglycerides (TRG) graph shows (Figure 1): that littermates on a normal diet had the lowest mean of 30 mg/dl, regardless of EGCG treatment. Ob/Ob HFD mice without EGCG had the highest mean of 90 mg/dl, indicating their impaired lipid clearance and increased risk of fatty liver disease and fibrosis. EGCG treatment significantly reduced triglyceride levels in Ob/Ob HFD mice, but they remained higher than in littermates, with a mean of 60 mg/dl. This indicates that EGCG may improve triglyceride metabolism in Ob/Ob HFD mice, but it is not enough to normalize their levels.

The Fasting Blood Sugar (FBS) graph shows (Figure 1): that littermates on a normal diet had the lowest mean of 100 mg/dl, regardless of EGCG treatment. Ob/Ob HFD mice without EGCG had the highest mean of 300 mg/dl, indicating their severe diabetic condition. EGCG treatment significantly reduced FBS levels in Ob/Ob HFD mice, but they remained higher than in littermates, with a mean of 180 mg/dl. This indicates that EGCG may improve blood sugar regulation in Ob/Ob HFD mice, but it is not enough to fully reverse their diabetic status.

The Insulin graph shows (Figure 1): that littermates on a normal diet had the lowest mean of 30 mg/dl, regardless of EGCG treatment. Ob/Ob HFD mice without EGCG had the highest mean of 90 mg/dl, indicating their marked insulin resistance and development of metabolic syndrome. EGCG treatment significantly reduced insulin levels in Ob/Ob HFD mice, and they reached a mean of 35 mg/dl, which is very close to the littermate control group readings. This indicates that EGCG may improve insulin sensitivity in Ob/Ob HFD mice, despite their elevated FBS levels.

Figure 1: EGCG improved biochemical assessment in the Ob/Ob HFD mice model.

The present study assessed biochemical indicators pertaining to lipid profiles (cholesterol, triglycerides), FBS and insulin in serum levels of mice models (littermate and Ob/Ob HFD) following an EGCG treatment. Data was reported as the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (± SEM), Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above the group comparisons, with”*” indicates p<0.05(significant difference). “**” indicating p<0.01(more significant difference) and “****” indicating p<0.0001(most significant difference). The “ns” indicates a non-significant difference.

| Group no. | Mouse no. | FBS

(mmol/L) |

Insulin (µU/L) | HOMA-IR

score |

Mean of HOMA-IR

score per group |

|

| 1 | 6.944 | 5.17 | 1.595 | |||

| 2 | 5 | 5.51 | 1.224 | |||

| Group. 1 | 3 | 4.777 | 5.68 | 1.205 | ||

| 4 | 6.111 | 4.31 | 1.170 | |||

| (Littermate | ||||||

| 5 | 6.944 | 4.99 | 1.540 | |||

| on a | 1.303 | |||||

| 6 | 5.111 | 5.51 | 1.251 | |||

| normal diet | ||||||

| 7 | 4.777 | 5.34 | 1.133 | |||

| without | ||||||

| 8 | 5.555 | 4.31 | 1.064 | |||

| treatment) | ||||||

| 9 | 5.166 | 5.85 | 1.343 | |||

| (Control | ||||||

| group). | 10 | 6.111 | 4.47 | 1.214 | ||

| 11 | 7.5 | 4.31 | 1.436 | |||

| 12 | 6.388 | 5.17 | 1.467 | |||

| 1 | 7.222 | 5.17 | 1.659 | |||

| Group. 2 | 2 | 6.777 | 4.82 | 1.451 | ||

| 3 | 5 | 5.68 | 1.262 | |||

| (Littermate | ||||||

| 4 | 4.888 | 5.51 | 1.197 | |||

| on normal | 1.411 | |||||

| 5 | 7.222 | 5.34 | 1.714 | |||

| diet | ||||||

| 6 | 6.944 | 4.82 | 1.487 | |||

| treated | ||||||

| 7 | 5.277 | 5.34 | 1.252 | |||

| with | ||||||

| 8 | 6.666 | 5.51 | 1.632 | |||

| EGCG) | ||||||

| 9 | 5 | 5.68 | 1.262 | |||

| 10 | 4.888 | 5.51 | 1.197 | |||

| 11 | 7.388 | 5.34 | 1.753 | |||

| 12 | 4.833 | 4.99 | 1.071 | |||

| 1 | 11.666 | 15.49 | 8.031 | |||

| 2 | 16.666 | 20.68 | 15.317 | |||

| Group.3 | 3 | 23.888 | 22.92 | 24.333 | ||

| 4 | 16.111 | 24.83 | 17.77 | |||

| (Ob/Ob HFD | ||||||

| 5 | 11.666 | 17.05 | 8.840 | |||

| animal not | 12.644 | |||||

| 6 | 16.666 | 15.16 | 11.229 | |||

| treated | ||||||

| 7 | 23.333 | 12.92 | 13.398 | |||

| with | ||||||

| 8 | 19.444 | 7.57 | 6.541 | |||

| EGCG) | ||||||

| 9 | 24.444 | 9.47 | 10.288 | |||

| 10 | 16.111 | 11.54 | 8.263 | |||

| 11 | 13.888 | 25.13 | 15.511 | |||

| 12 | 16.111 | 17.05 | 12.208 |

| 1 | 10.555 | 3.78 | 1.773 | |||

| 2 | 9.222 | 2.58 | 1.057 | |||

| Group.4 | 3 | 9.277 | 3.96 | 1.632 | ||

| 4 | 8.333 | 7.57 | 2.803 | |||

| (Ob/Ob HFD | ||||||

| 5 | 10.555 | 5.85 | 2.744 | |||

| animal | 2.871 | |||||

| 6 | 9.222 | 10.32 | 4.229 | |||

| treated | ||||||

| 7 | 9.277 | 5.85 | 2.412 | |||

| with | ||||||

| 8 | 9.222 | 11.85 | 4.856 | |||

| EGCG) | ||||||

| 9 | 9.333 | 13.26 | 5.500 | |||

| 10 | 8.611 | 4.47 | 1.710 | |||

| 11 | 10.455 | 7.24 | 3.364 | |||

| 12 | 9.722 | 5.51 | 2.380 |

The HOMA-IR score was calculated according to the following equation: HOMA-IR = (Fasting Insulin (µU/L) * Fasting Glucose (mmol/L)) / 22.5.

In our experiment the readings of FBS and fasting Insulin were in mg/dl due to the availability of kits, so, readings of fasting insulin in mg/dl were converted to µU/L using the following conversion formula:

Insulin (μU/L)= Insulin (mg/dL)×1000

————————————

Molecular Weight of Insulin (g/mol)

Readings of FBS in mg/dl were converted to mmol/L using the following conversion formula:

Blood Glucose (mmol/L) = Blood Glucose (mg/dL)

————————-

18.0159

HOMA-IR stands for Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance, which is a simple method to estimate the degree of insulin resistance in the body by assessing serum levels of fasting insulin and fasting blood sugar.

This condition- insulin resistance- can increase the risk of various metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and liver fibrosis.

There is no consensus on the cut-off values for HOMA-IR to define insulin resistance, but some general ranges are:

- HOMA-IR < 1: optimal insulin

- HOMA-IR 1-1.9: normal or slightly reduced insulin

- HOMA-IR 2-2.9: early insulin

- HOMA-IR > 9: significant insulin resistance.

We categorized our experimental groups based on their HOMA-IR values as follows:

- Group 1: normal or slightly reduced insulin sensitivity (Mean HOMA-IR score=1.303), Littermate not treated with EGCG.

- Group 2: normal or slightly reduced insulin sensitivity (Mean HOMA-IR score=1.411), Littermate treated with EGCG.

- Group 3: significant insulin resistance (Mean HOMA-IR score=12.644), Ob/Ob HFD untreated.

- Group 4: early insulin resistance (Mean HOMA-IR score=2.871), Ob/Ob HFD treated with

Group 3 had the highest HOMA-IR values, indicating a significant degree of insulin resistance, while Group 1 and Group 2 had similar and lower HOMA-IR values, indicating normal or slightly reduced insulin sensitivity. This suggests that obesity, high-fat diet, and metabolic syndrome in Group 3 negatively affected their insulin response, while EGCG treatment in Group 2 may have a minor positive effect.

Group 4 consisted of obese mice fed with a high-fat diet (Ob/Ob HFD) and treated with EGCG. Group 4 had a mean HOMA-IR value of 2.871, which was lower than Group 3’s mean value of 12.644, but higher than Group 1 and Group 2’s mean values of 1.411 and 1.303, respectively. This implies that Group 4 had an early degree of insulin resistance, which was improved by EGCG treatment, but not completely normalized.

The substantial difference in HOMA-IR value between Group 3 and Group 4 was attributed to the administration of EGCG, which is a green tea polyphenol with anti-obesity and anti- diabetic effects. Therefore, Group 4, which received EGCG treatment, had a lower HOMA-IR value and early insulin resistance, compared to Group 3, which did not receive EGCG treatment and had a high HOMA-IR value and significant insulin resistance. This demonstrates that EGCG can partially reverse the detrimental effects of obesity, high-fat diet, and metabolic syndrome on insulin sensitivity and response. However, EGCG alone may not be enough to normalize the HOMA-IR value and insulin sensitivity, as Group 4 still had a higher HOMA- IR value and a lower insulin sensitivity than Group 1 and Group 2.

Assessment of inflammatory and fibrotic profiles in Ob/Ob HFD -induced liver damage mice model- and Littermate mice-control group- following treatment with EGCG.

EGCG is a compound that has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Ob/Ob HFD animals are obese mice with a mutation in the leptin gene that are fed a high-fat diet. We adopted this model which was used as a model for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition characterized by fat accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver to confirm data obtained from the effects of EGCG on liver injury and fibrosis with an additional mice model.

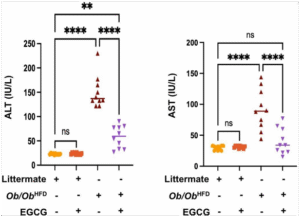

Based on the graphs in Figure 2; we detected the following observations in serum inflammatory profiles:

- Littermate on a normal diet treated with EGCG has low ALT and AST serum levels, indicating healthy liver function.

- Littermate on a normal diet without EGCG also has low ALT and AST serum levels, suggesting that EGCG does not have a significant effect on liver function in normal

- Ob/Ob HFD animal not treated with EGCG has very high ALT and AST serum levels, indicating severe liver damage and inflammation (with mean values of 140 IU/L and 90 IU/L for ALT and AST respectively). This is consistent with the NAFLD phenotype of this model.

- Ob/Ob HFD animal treated with EGCG has significantly lower ALT and AST serum levels than the untreated group (with mean values of 60 IU/L and 35 IU/L for ALT and AST respectively), implying that EGCG has a protective effect on hepatocytes and liver function in NAFLD mice(p<0.0001). This is supported by some studies that show that EGCG can reduce liver fat accumulation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory cytokines in NAFLD models.

The Ob/Ob HFD groups have significantly higher ALT and AST serum levels than the littermate groups(p<0.0001), and the EGCG-treated groups have significantly lower ALT and AST serum levels than the non-treated groups.

Ob/Ob HFD treated with EGCG showed a significant amelioration of 2.3 folds in ALT levels and 2.5 in AST levels (by comparison mean values among Ob/Ob HFD groups).

To summarize, the graphs in Figure 2 demonstrate that Ob/Ob HFD animals have impaired liver function compared to littermates which is reflected by higher ALT and AST serum levels and

that EGCG treatment has a beneficial effect on liver function in NAFLD mice by mitigating their liver injury enzymes levels.

EGCG’s protective effects on the liver are likely due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, its regulation of cell signaling pathways, its enhancement of detoxification processes, and its protection against mitochondrial dysfunction.

Figure 2: EGCG ameliorates liver injury in the Ob/Ob HFD mice model.

Serum levels of ALT, and AST as indicators of liver injury and damage were assessed using an ELISA kit; in littermate and Ob/Ob HFD mice following an EGCG treatment. Data was reported as the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (± SEM). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above the group comparisons, with “**” indicating p<0.01 and “****” indicating p<0.0001, suggesting a highly significant difference. The “ns” indicates a non-significant difference.

Effect of EGCG on fibrosis markers in normal and obese animals

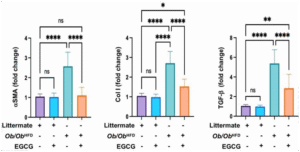

Based on the graphs in Figure 3; fold change values of three fibrosis markers: liver alpha- smooth muscle actin (αSMA), collagen I (Col I), and Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF- β) were quantified among four different groups of mice to validate the presence of liver fibrosis using RT-PCR.

We used two types of animals: littermates on a normal diet and Ob/Ob HFD animals that are obese and have liver fibrosis-. We divided them into four groups:1) littermate on a normal diet without EGCG (purple), 2) littermate on a normal diet treated with EGCG (blue),3) Ob/Ob HFD mice not treated with EGCG (green), and 4) Ob/Ob HFD mice treated with EGCG (orange).

The graphs exhibited in Figure 3 show that:

We used Ob/Ob HFD animals as a model of liver fibrosis induced by obesity. These animals (group 3) showed significantly higher levels of α-SMA, Col-I, and TGF-β, which are markers of fibrosis, than littermates on a normal diet -groups 1 and 2- (p<0.0001).

To test the antifibrotic effect of EGCG, we measured the levels of these markers in Ob/Ob HFD animals treated with EGCG (group 4) and compared them with those in untreated Ob/Ob HFD animals (group 3).

Treatment with EGCG (group 4) significantly reduces the levels of all three fibrosis markers in obese animals, indicating a potent antifibrotic effect of EGCG.

The percentage of reduction in fibrosis markers due to EGCG treatment is more remarkable in obese animals (group 4) than in normal animals (group 2), suggesting that EGCG has a greater therapeutic potential in treating fibrotic diseases in obese mice models.

- α-SMA levels are significantly lower in group 4 than in group 3, indicating a reduction in fibrosis. The fold change value of α-SMA in group 4 is 1, while in group 3 it is 2.5 which means that α-SMA levels are 60% lower in group 4 (Ob/Ob HFD treated with EGCG) than in group 3(p<0.0001). This suggests that EGCG inhibits the activation of hepatic stellate cells and the production of extracellular matrix proteins in the liver tissue.

- Col-I expression is also significantly lower in group 4 than in group 3, indicating a reduction in collagen synthesis. The fold change value of Col-I in group 4 is 1.5, while in group 3 it is 2.5 which means that Col-I expression is 40% lower in group 4 (Ob/Ob HFD treated with EGCG) than in group 3(p<0.0001). This suggests that EGCG blocks the cross- linking of collagen fibers and the accumulation of scar tissue in the liver tissue.

- TGF-β levels are similarly lower in group 4 than in group 3, indicating a reduction in TGF- β signaling. The fold change value of TGF-β in group 4 is 2.5, while in group 3 it is 5.5 which means that TGF-β levels are 54.5% lower in group 4 (treated with EGCG) than in group 3(p<0.0001). This suggests that EGCG interferes with the binding of TGF-β to its receptor and the activation of the downstream pro-fibrotic pathway in the liver tissue.

These results demonstrate that EGCG exposure has a potent antifibrotic effect by inhibiting lysyl oxidase-like2 (LOXL2) and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1) receptor kinase1 which in role modulates the expression of key fibrosis markers in obese animals.

Thus, our results indicate EGCG as a potential target for delaying and inhibiting liver fibrosis through improving lipids profile and decaying expression of fibrosis markers.

Figure 3: EGCG ameliorates liver fibrosis in the Ob/Ob HFD mice model.

Three markers of fibrosis were being evaluated using RT-PCR: α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin), Collagen I (Col I), and TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor-beta). Data was reported as the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (± SEM), Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above the group comparisons, with”*” indicating p<0.05(significant difference). “**” indicating p<0.01(more significant difference) and “****” indicating p<0.0001(most significant difference). The “ns” indicates a non-significant difference.

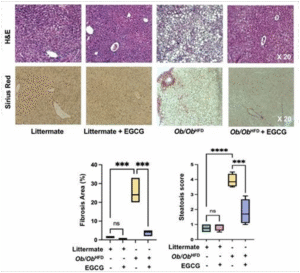

Histopathological assessment for evaluation degree of steatosis and fibrosis in liver specimens for Ob/Ob HFD – induced liver damage mice model – and Littermate mice-control group- following treatment with EGCG.

Based on Figure 4. exhibits histopathological findings from our study examining the effects of EGCG on liver pathology in the Ob/Ob HFD mouse model. The top row shows liver tissue sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). The bottom row shows sections stained with Sirius Red.

The four sets of images correspond to the following groups:

- Littermate control mice with no HFD or EGCG

- Littermate control mice treated with

- Ob/Ob HFD, likely have developed some degree of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

- Ob/Ob HFD treated with

The H&E stained sections show the liver architecture, including the hepatocytes and sinusoidal spaces. In healthy liver tissue, the architecture is orderly, while diseased liver tissue often shows disrupted architecture, inflammatory cells, and signs of cell damage. The Sirius Red staining highlights the extent of fibrosis, with more intense red staining indicating more collagen deposition and fibrosis.

Histopathological Assessment with Hematoxylin and Eosin(H&E):

The comparative histological examination of liver sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) was performed to evaluate morphological alterations indicative of liver injury.

· The liver sections from both control groups (Naïve Littermate mice):

Exhibits normal hepatic architecture with well-preserved hepatocyte structure and no evident signs of steatosis, ballooning degeneration, inflammatory reaction, or any other pathological findings.

- The liver section from the Ob/Ob HFD (Ob/Ob HFD Not treated with EGCG):

Presents substantial morphological changes characterized by disrupted hepatic architecture, Extensive macro vesicular steatosis typically presents as large, clear vacuoles within

hepatocytes, displacing the nucleus to the periphery suggesting lipid accumulation, associated with ballooning degeneration and cytoplasmic vacuolization.

Infiltration of inflammatory cells is detected as clusters of small, darkly staining nuclei within the sinusoidal spaces and around the portal areas.

- The liver section from Treatment Group (Ob/Ob HFD + EGCG):

Exhibits less degeneration and better-preserved cellular integrity reflected as less swollen, with more eosinophilic (pink) staining cytoplasm, associated with a noticeable reduction in both macro and microvesicular steatosis noticed by a reduction in the clear, circular spaces, implying a decrease in lipid accumulation within the hepatocytes.

Attenuation of inflammatory reaction is reflected by a reduction in the density of dark- staining cells which present a decrease in inflammatory cell infiltrates, with less clustering around portal tracts and within the parenchyma.

The overall liver architecture seems better preserved with the restoration of hepatocyte morphology with reduced ballooning, indicating improved cell health, evident by more regular, polygonal shapes of hepatocytes with centrally placed nuclei, with more regular hepatocyte alignment and less disruption of the sinusoidal spaces.

Histopathological Assessment with Sirius Red staining:

- The liver sections from both control groups (Naïve Littermate mice):

The Sirius Red staining shows very minimal collagen deposition, as indicated by the light staining in the liver tissue. The collagen fibers, which Sirius Red targets, are scarce and limited to the areas surrounding the portal spaces, which is typical for normal liver architecture.

EGCG treatment does not significantly affect collagen deposition in the liver of normal, healthy mice.

- The liver section from the Ob/Ob HFD (Ob/Ob HFD Not treated with EGCG):

Exhibits a pronounced increase in collagen deposition, as indicated by the extensive red staining throughout the tissue within the liver parenchyma, around central veins, and in the portal areas, consistent with fibrosis.

The liver architecture showed signs of distortion due to the extensive fibrotic tissue replacing normal parenchyma, leading to nodule formation with moderate bridging fibrosis.

- The liver section from Treatment Group (Ob/Ob HFD + EGCG):

presents a noticeable reduction in the intensity and extent of the red staining, suggesting less collagen accumulation and thus reduced fibrosis compared to the Ob/Ob HFD group, but still a marked presence when compared to the Littermate groups. This indicates that while EGCG treatment seems to mitigate some of the fibrosis caused by the high-fat diet in obese mice, it does not completely reverse it.

The liver architecture may appear more normal with less nodularity and bridging, indicating that the EGCG treatment has a protective effect against the development of fibrosis.

Quantitative Graphs Comparison (Figure 4.):

- The “Fibrosis Area (%)” graph quantifies the extent of fibrosis observed in the Sirius Red stained sections. The Littermate groups (with or without EGCG) show negligible fibrosis. In contrast, the Ob/Ob HFD group has a high percentage of fibrosis area (with a mean of 25%), which is significantly reduced in the Ob/Ob HFD + EGCG group(p<0.001) with a mean of 5%, although not to the levels seen in the Littermate groups.

- The “Steatosis Score” graph likely represents a qualitative assessment of fat accumulation in the liver, which is not directly shown in the Sirius Red images but could be inferred from the H&E-stained sections. Like fibrosis, the steatosis is significantly higher in the Ob/Ob HFD group compared to the Littermate(p<0.0001), and EGCG treatment in the Ob/Ob HFD group reduces the steatosis score(p<0.001), indicating a therapeutic

Overall Histopathological Impression: The Sirius Red stained specimens indicate that the Ob/Ob HFD group experienced significant liver fibrosis, a common pathological feature of non- alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is often associated with obesity and a high-fat diet. The EGCG treatment appears to have a hepatoprotective effect, reducing the extent of fibrosis in the obese high-fat diet mice model. This therapeutic effect is also reflected in the reduction of steatosis, as shown in the quantitative graphs. The histopathological findings suggest that EGCG may have potential as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of diet-induced liver damage, although it does not completely normalize the histological features.

Figure 4: EGCG improved liver histopathological profile in the Ob/Ob HFD mice model. Liver specimens underwent histopathological examination with H&E and Sirius’s red staining assessed by quantitative graphs measuring fibrosis area percentage and steatosis score. Data was reported as the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (± SEM), Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above the group comparisons, with “***” indicating p<0.001(significant difference) and “****” indicating p<0.0001(most significant difference). The “ns” indicates a non-significant difference.

Assessment of total serum bile acids levels in Ob/Ob HFD -induced liver damage mice model- and Littermate mice-control group- following treatment with EGCG.

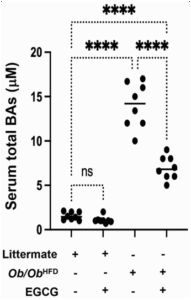

The scatter plot (Figure 5. ) provides a visualization of an experimental analysis examining the impact of Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) on serum total bile acids (BAs) in different mice models. The vertical axis of the plot quantifies serum total BAs concentration in micromoles per liter (µM), ranging from 0 to 20 µM. The horizontal axis segregates the data into four distinct experimental groups based on genotype and treatment: (1) wild-type littermate controls without high-fat diet (HFD) or EGCG treatment, (2) wild-type littermate controls treated with EGCG, (3) Ob/Ob HFD without EGCG treatment, and (4) Ob/Ob HFD treated with EGCG.

Based on Figure 5. Exhibits the following findings:

- Naive littermate controls not treated with EGCG exhibit baseline serum bile acids (BAs) levels, with all individual measurements falling at or below 5 µM, suggesting a narrow range of physiological variation in the absence of external interventions.

- The addition of EGCG to the Naive littermate controls does not result in a statistically significant alteration in serum BAs levels, as denoted by “ns,” indicating that under normal dietary conditions, EGCG does not exert a substantial modulatory effect on serum BAs

- Ob/Ob HFD exhibits a significant elevation in serum BAs levels (mean values above 15 µM), which implies that the obese phenotype combined with a high-fat dietary regimen markedly influences bile acid trafficking metabolism (p<0.0001).

- Treatment with EGCG in Ob/Ob HFD leads to a notable reduction in serum BAs levels when compared to their untreated counterparts (p<0.0001). However, despite this reduction, the serum BAs concentration remains elevated compared to both groups of wild-type littermate

The data collectively suggest a genotype and diet-dependent modulation of serum BAs by EGCG. Specifically, the intervention appears to mitigate the diet-induced increase in serum BAs observed in the Ob/Ob mice, signifying a potential therapeutic benefit of EGCG in conditions characterized by elevated bile acid synthesis or impaired bile acid clearance associated with obesity and high-fat diet consumption. The lack of a significant effect in the wild-type controls may reflect a ceiling effect of EGCG activity or a differential baseline regulation of bile acid metabolism that is not easily perturbed by EGCG in a non-obese, standard diet context.

Figure 5: EGCG mitigates total serum bile acids levels in Ob/Ob HFD mice model.

Serum levels of bile acids(µM) as an indicator of hepatic stress (NAFLD) and cholestasis were assessed using a bile acid ELISA kit detector. Data was reported as the mean value along with the standard error of the mean (± SEM), Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above the group comparisons, with “****” indicating p<0.0001(most significant difference). The “ns” indicates a non-significant difference.

Discussion and conclusion

The research explored the efficacy of Epigallocatechin 3-Gallate (EGCG), a key catechin in green tea, in mitigating metabolic deterioration in Ob/Ob mice subjected to a high-fat diet (HFD). This model simulates human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), characterized by obesity, insulin resistance, and hepatic fat accumulation. The study compared the effects of EGCG treatment against untreated controls in both Ob/Ob HFD mice and normal littermates on standard diets. The outcomes revealed EGCG’s potential in addressing metabolic issues linked to NAFLD.

Our 12-week study showed a great effect of EGCG in ameliorating liver fibrosis, and metabolic profile, especially bile acid trafficking through sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP), a major BAs transporter. thus, decreasing bile acid levels in the blood and its related effect on liver injury, this was achieved through observing several enzymatic and fibrotic marker changes upon treatment with EGCG.

Our results showed that EGCG has a significant effect on metabolic profile in Ob/Ob HFD as the EGCG treatment significantly improved the lipid profile (reduced cholesterol and triglycerides), lowered fasting blood sugar (FBS), and improved insulin sensitivity in the Ob/Ob HFD mice, but it did not completely normalize these markers. This suggests that EGCG can partially reverse the metabolic problems caused by the high-fat diet.

On the level of liver damage, EGCG treatment significantly reduced the levels of liver enzymes ALT and AST, which are markers of liver damage. This indicates that EGCG can protect the liver from the harmful effects of a high-fat diet.

Fibrosis is the scarring of the liver, which is a hallmark of advanced NAFLD. Our research observed a notable anti-fibrotic impact of EGCG in mice induced with Ob/Ob HFD, we noticed an improvement in liver fibrotic markers αSMA, collagen I, and TGF-β. This suggests that treating with EGCG may serve as a potential strategy against fibrosis by mitigating the activation of hepatic stellate cells through the reduction of free radicals, which are recognized as a characteristic aspect of chronic liver disease.

The Histopathological analysis which involves examining liver tissue under a microscope, confirmed that EGCG treatment reduced the amount of fat buildup (steatosis) and fibrosis in the livers of the Ob/Ob HFD mice which was assessed by H&E and Sirius Red staining respectively. The reduced degeneration and improved preservation of cellular integrity are evident as minimal swelling and increased pink staining of the cytoplasm. Additionally, there is a noticeable decrease in both macro and micro-vesicular steatosis, characterized by a reduction in clear, circular spaces, indicating a decline in lipid accumulation within hepatocytes. This further supports the idea that EGCG can protect the liver from damage caused by the high-fat diet.

The main findings of this study reveal compelling evidence supporting the positive impact of EGCG treatment on various metabolic health indicators in Ob/Ob HFD, a model simulating non- alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Notably, EGCG treatment resulted in significant enhancements, including improved lipid profiles marked by reduced cholesterol and triglycerides, lowered fasting blood sugar (FBS), enhanced insulin sensitivity, decreased levels of liver damage markers (ALT and AST), reduced fibrosis markers (α-SMA, collagen I, TGF- β), and a diminished presence of steatosis (fatty buildup) in the liver.

Comparisons with other studies reinforce these findings, aligning with prior research demonstrating EGCG’s positive effects on metabolic health and liver function in animal models of NAFLD. For instance, a 2016 study published in Jpet indicated that EGCG treatment improved insulin sensitivity and mitigated hepatic steatosis in mice subjected to a HFD. However, it is crucial to acknowledge conflicting outcomes in some studies, where specific models or dosages did not yield significant effects of EGCG.

The study’s potential policy implications underscore its contribution to the mounting body of evidence advocating for the advantages of EGCG in promoting metabolic health and preventing/managing NAFLD. While additional research is imperative to determine the optimal EGCG dosage and ensure safety for human consumption, these findings could shape future dietary recommendations and potentially lead to the development of EGCG-based interventions for NAFLD. Public health policies encouraging dietary patterns rich in fruits, vegetables, and green tea, natural sources of EGCG, may prove beneficial for NAFLD prevention and management.

The strengths of the study lie in its utilization of a well-established animal model for NAFLD (Ob/Ob mice) with both treated and control groups. The comprehensive measurement of a wide range of metabolic and liver health markers provides a robust understanding of EGCG’s effects, further supported by histopathological analysis confirming its protective impact on liver tissue.

However, the study has limitations, primarily being conducted in mice, necessitating caution in extrapolating results directly to humans. Long-term safety and optimal EGCG dosage for human consumption remain undetermined. Nevertheless, our study was conducted on a relatively small sample population (48 mice divided into four groups) due to limitations in time and budget; making it a crucial necessity for further research studies to be conducted with a

larger sample population and capabilities to confirm precisely our results in this study. The study primarily focused on EGCG’s effects on specific markers and did not delve into the underlying mechanisms in detail.

Future directions for research include investigating the precise mechanisms through which EGCG exerts its beneficial effects, determining optimal human dosage and long-term safety, conducting clinical trials to assess EGCG’s effectiveness for NAFLD prevention and treatment in humans, and exploring potential interactions with other dietary components or medications. Overall, this study provides promising evidence for the potential benefits of EGCG in enhancing metabolic health and safeguarding against liver damage in the context of NAFLD, emphasizing the need for further research to translate these findings into effective strategies for human health promotion and disease prevention.

References

- Cencic A, Chingwaru The role of functional foods, nutraceuticals, and food supplements in intestinal health. Nutrients [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 Mar 23];2(6):611–25. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22254045/

- Gan RY, Li H Bin, Sui ZQ, Corke Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. https://doi.org/101080/1040839820161231168 [Internet]. 2017 Apr 13 [cited 2023 Mar 23];58(6):924–41. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10408398.2016.1231168

- Prasanth M, Sivamaruthi B, Chaiyasut C, Tencomnao T. A Review of the Role of Green Tea ( Camellia sinensis) in Antiphotoaging, Stress Resistance, Neuroprotection, and Autophagy. Nutrients [Internet]. 2019 Feb 23 [cited 2023 Mar 23];11(2):474. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30813433/

- Gan RY, Li HB, Sui ZQ, Corke Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr [Internet]. 2018 Apr 13 [cited 2023 Mar 23];58(6):924–41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27645804/

- Khan N, Afaq F, Saleem M, Ahmad N, Mukhtar Targeting multiple signaling pathways by green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Cancer Res [Internet]. 2006 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Mar 23];66(5):2500–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16510563/

- Negri A, Naponelli V, Rizzi F, Bettuzzi S. Molecular Targets of Epigallocatechin-Gallate (EGCG): A Special Focus on Signal Transduction and Nutrients [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Mar 23];10(12). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30563268/

- Mukhtar H, Ahmad Tea polyphenols: prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2023 Mar 23];71(6 Suppl). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10837321/

- Afzal M, Safer AM, Menon Green tea polyphenols and their potential role in health and disease. Inflammopharmacology [Internet]. 2015 Aug 27 [cited 2023 Mar 23];23(4):151–61. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26164000/

- Khalatbary AR, Khademi E. The green tea polyphenolic catechin epigallocatechin gallate and neuroprotection. Nutr Neurosci [Internet]. 2020 Apr 2 [cited 2023 Mar 23];23(4):281–94. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30043683/

- Brown AL, Lane J, Holyoak C, Nicol B, Mayes AE, Dadd Health effects of green tea catechins in overweight and obese men: a randomised controlled cross-over trial. British Journal of Nutrition [Internet]. 2011 Dec 28 [cited 2023 Mar 23];106(12):1880–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/health-effects-of- green-tea-catechins-in-overweight-and-obese-men-a-randomised-controlled-crossover- trial/764DCFAEE95DED5263D9444388CDB3FE

- Almatrood SA, Almatroudi A, Khan AA, Alhumaydh FA, Alsahl MA, Rahmani Potential therapeutic targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), the most abundant catechin in green tea, and its role in the therapy of various types of cancer. Molecules. 2020 Jul 1;25(14).

- Mokra D, Joskova M, Mokry Therapeutic Effects of Green Tea Polyphenol (‒)-Epigallocatechin-3- Gallate (EGCG) in Relation to Molecular Pathways Controlling Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2022 Dec 25 [cited 2023 Mar 23];24(1). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36613784

- Legry V, Francque S, Haas JT, Verrijken A, Caron S, Chávez-Talavera O, et Bile Acid Alterations Are Associated with Insulin Resistance, but Not With NASH, in Obese Subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Mar 23];102(10):3783–94. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/28938455

- Yang F, Xu W, Wu L, Yang L, Zhu S, Wang L, et NTCP Deficiency Affects the Levels of Circulating Bile Acids and Induces Osteoporosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 22;13:1048.

- Slijepcevic D, Kaufman C, Wichers CGK, Gilglioni EH, Lempp FA, Duijst S, et Impaired uptake of conjugated bile acids and hepatitis b virus pres1-binding in na(+) -taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide knockout mice. Hepatology [Internet]. 2015 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Mar 24];62(1):207–19. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25641256/

- Salhab A, Amer J, Lu Y, Safadi Sodium+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide as target therapy for liver fibrosis. Gut [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Mar 24];71(7):1373–85. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34266968/

- Ying L, Yan F, Zhao Y, Gao H, Williams BRG, Hu Y, et (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and atorvastatin treatment down-regulates liver fibrosis-related genes in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol [Internet]. 2017 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Mar 23];44(12):1180–91. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28815679/

- Ninfali P, Antonelli A, Magnani M, Scarpa Antiviral Properties of Flavonoids and Delivery Strategies. Nutrients 2020, Vol 12, Page 2534 [Internet]. 2020 Aug 21 [cited 2023 Mar 24];12(9):2534. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/9/2534/htm

#EGCG #EpigallocatechinGallate #Polyphenols #HighFatDiet #MetabolicSyndrome #MetabolicHealth #ObesityResearch #DietInducedObesity #HFDModel #MouseModel #C57BL6 #InsulinResistance #HOMAIR #LipidMetabolism #GlucoseMetabolism #OxidativeStress #Inflammation #NaturalCompounds #Nutraceuticals #FunctionalFoods #GreenTeaPolyphenols #ExperimentalStudy #PreclinicalResearch #BiomedicalResearch #MetabolicDisorders #LiverHealth #NAFLD #HepaticSteatosis #CardiometabolicHealth #Endocrinology #MolecularNutrition #PreventiveMedicine #TranslationalResearch #DietaryIntervention #ChronicDisease #FatMetabolism #EnergyHomeostasis #InsulinSensitivity #Antioxidants #AntiInflammatory #TherapeuticPotential #LifestyleDiseases #MetabolicDelay #NutritionScience #HealthResearch #PreventionStrategy #AnimalStudy #BiologicalMechanisms