Child Nutrition During the Pandemic: The Impact of Work-Status

Unified Nursing Research, Midwifery & Women’s Health Journal

Volume 1, Issue 3, January 2023, Pages: 01-11

Received: October 5th, 2022, Reviewed: October 21st, 2022, Accepted: November 3rd, 2022, Published: January 13, 2023

Unified Citation Journals, Nursing 2023, 1(3) 1-15; https://doi.org/10.52402/Nursing205

ISSN 2754-0944

Authors: Najla Al Nassar-Moyles, DHSc, MS, RDN Shirley Matenda, MS, CD, RDN, CDCES, Sarah Thomas-Anderson, MS, RDN, CCRP

*Corresponding Author: Najla Al Nassar-Moyles

Download PDFKeywords: COVID-19, Child Nutrition, Remote Work, Pandemic

ABSTRACT:

Objective: This study has been conducted to examine the impact of parent work status during the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID-19) on child nutrition behavior.

Setting: COVID-19 changed the way families purchase and prepare food. Online schooling impacted children’s eating habits as well. COVID-19 impact on child nutrition behavior has not been thoroughly investigated.

Intervention(s): The study was conducted by means of a survey which was posted online for parents via social media groups (e.g. Facebook) during May 2021 thru August 2021.

Participants: The study targeted parents with children between the ages of 1 to 17, living at home.

Analysis: Bivariate analysis was used to assess changes in child-nutrition behavior since COVID-19 started.

Main outcome measure(s): Percentage of parents reporting child(ren) changes in food volume, food type, supplement use and eating pattern by change in parent work-status.

Results: Only 13 % of parents felt changes were due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Parents working full-time reported the greatest impact on child nutrition behavior.

Conclusions and implications: Governments need to consider child food security during COVID-19. We recommended specific food and nutrition resources to better assist children during COVID-19 and future pandemics.

INTRODUCTION

Children have been one of the most disadvantaged age groups in terms of nutrition during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period (1). The United Nations World Food Program estimated that 265 million people may face acute food insecurity by the end of 2020, which is almost double the number of people under severe threat of food insecurity around the world (2). There is an association between periods of compromised nutrition during early childhood development and eating pathology (2).

Social distancing and stay-at-home orders issued across the globe under COVID-19 protocols decreased physical activity among children (3). López-Bueno et al. (1) found that online video games usage has increased since the start of the pandemic. Increased screen time is associated with childhood overweight and obesity. Several health-related behaviors (such as screen exposure, physical activity, sleep patterns, body composition, and environmental influence) may be exacerbated by social isolation (1). While public parks and playgrounds were available during the pandemic, many families avoided them, further contributing to an increase in sedentary lifestyles (3).

The European Pediatric Association–Union of National European Pediatric Societies and Associations (EPA-UNEPSA) created a collaborative working group with Chinese academic institutions and medical centers to exchange information and scientific knowledge (4). The purpose of this commentary by the China-EPA-UNEPSA working group is to increase awareness of children’s psychological needs during the COVID-19 pandemic and present an early report of collected data in affected areas. The family’s role in early recognition and intervention of the adverse effect is the focus of the working group (4).

OBJECTIVE

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way families purchase and prepare food. The transition to online schooling has impacted children’s eating habits as well. As this is a new situation, the impact this pandemic has had on the oral intake of children has not been thoroughly investigated. This study has been conducted to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the oral consumption and nutritional status of children.

RESEARCH DESIGN

The study was conducted in the United States of America from 18 May 2021 to 15 August 2021. It was conducted by means of a survey which was posted online for parents via social media groups (such as Facebook for example). For the purposes of this survey, the term ‘parents’ includes parents, caregivers and guardians. Participation was voluntary, subjects completed a consent form and agreed to participation before completing the survey. In addition, participants had the ability to share the survey which enabled a wider pool of respondents. The study targeted parents with children between the ages of 1 to 17, living at home. Parents had to be 21 years of age or older. Only one survey could be completed by each family. The questionnaire was administered via Survey Monkey allowing for a wide variety of family groups representing each state in the US to be included. The questionnaire addressed changes in intake volume, food consumed from various food categories, supplement use, and changes in overall eating habits during the pandemic (2020-2021).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Working hours during the pandemic: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic many people began working from home, including many who were simultaneously caring for children. We reviewed several studies to determine the impact this had on households. The Department of Child and Family Science, California State University, Fresno, CA, found that stay-at-home parents and parents who were working remotely from home were less likely to buy convenience foods (5). Some families found themselves to be cooking and consuming more meals together, due to being home for longer periods. An increase in family meals help family members to feel more connected, has been associated with an increased consumption of produce, and an improvement in diet quality (5).

Krukowski et al. (6) looked at the associations of gender and parental work status amongst faculty staff, with self-reported academic productivity before and during the pandemic. While there was no significant difference in the hours worked per week by gender, the age of the children in the home did impact the hours those adults worked. Parents with children aged 0–5 years reported significantly fewer work hours compared with parents of children between the ages of 6-17 years. Women also completed fewer assignments in comparison to men. Parents with children older than five years at home, or without children at home, either reported significant increases in outputs or stable productivity (6).

Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Pivari, et al. (7) completed a survey among Italian respondents (n=3533, ages 12-86 yr., 76.1% female) in April 2020 following seven weeks of lockdown, to determine the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating habits and lifestyle changes among the Italian population. At the time, Italy was the world’s second worst-affected country in the COVID-19 pandemic. 34.4% of respondents felt that they had increased appetite, while 17.7% had reduced appetite. There was no significant difference between groups who felt they ate healthier food (such as fruit, vegetables, nuts and legumes for example) or less healthy options (7).

Food Security Concerns: Two recent US surveys carried out by Rundle et al. (3) showed that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to higher rates of food insecurity in households with children compared with previous years (2). According to the COVID-19 Impact Survey (8) by end of April 2020 around 34 % of households with a child ≤ 18 years old were food insecure, compared with about 15% in 2018. In addition, the Survey of Mothers with Young Children (8) reported that since the outbreak of the pandemic, food insecurity was reported in about 40% of mothers with children ≤ 12 years old. (2). Over 30 million children receive free or subsidized school lunches; this means that in the summer months, during vacation, food insecurity rates are higher (3). Rundle et al. (3) projected that just 3 days of school closures in Philadelphia could result in more than 405,000 missed meals among school-aged children. Some communities were delivering meals utilizing school buses (3).

The effect of the COVID pandemic on the content of meals: Changes in employment and working conditions not only affect income, but also food security, behavior, and other factors (10). Since March 2020, 27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children (10). COVID-19 pandemic has raised concern about the significant impact of food insecurity and eating pathology (2). Food insecurity is linked with disordered eating, such as excessive nighttime eating, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. (2) Another study aimed to evaluate the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on food parenting practices looking specifically at parents who have young children. The results suggest that effects of the COVID-19 pandemic stress on parents is reflected on child intake as less structure and more indulgence (11).

In a cross-sectional, observational study by Adams, Caccavale, Smith, and Bean (12), which measured food security status, home food environment and parent feeding practices pre and post pandemic, the researchers found that more than half the families experienced a decrease in income. Approximately 30% of the households that were food secure before the pandemic experienced low or very low food security during the pandemic and approximately 46% of the households with low food security before the pandemic experienced very low food security after the pandemic (12). Lockdown conditions impacted how meals were prepared. Majority of the participants reported a decrease in fast-food and pre-prepared meals, but an increase in home-cooked meals (12). There were also many families who reported an increase in the total amount of food at home. One-third of the families reported an increase in high-calorie snacks and sweets while almost half reported an increase in processed foods (12). Alternately, the study also indicated that some children had greater access to healthy foods at home with an increase in fresh foods for 37% of the families (12).

The effect of the COVID pandemic on snacking: Without the structure provided in the school environment, some children may begin to increase their snack intake. A study in France was conducted among parents with children between the ages of 3-12 that looked at changes in children’s eating behaviors (13). These changes weren’t linked to causes other than the COVID-19 lockdown. Sixty percent of the parents reported a change in eating behaviors in their child(ren) (13).

In relation to snacking, both the mid-afternoon snack and snack/drinks in between meals were studied. In France, the mid-afternoon snack is considered to be a meal for children. They found that there was an increase in the frequency of snacking between meals among the children. (13) Fifteen percent of the children had an increase in the mid-afternoon snack with a significant increase candy, sweetened beverages, baked goods, processed snacks, dairy products, fruits and nuts. (13) The results indicated that boredom was a factor linked to emotional overeating and increasing snack frequency between meals. Changes in parental feeding practices were identified, such as a decrease in feeding rules for unhealthy foods. Parents also reported an increase in buying pleasurable, sustainable, and convenient foods (13).

A Canadian study evaluated changes in health behaviors post-COVID-19 pandemic among a subset of middle-income Canadian families of young children, average age = 6 years, n = 310 children (14). Parents noticed changes in eating behaviors among 51% of children since the pandemic. The most reported eating behaviors included more food being consumed among 42% of children, and more snack foods being eaten among 55% of children (14). Rundle et al. (3) argued that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates all the risk factors for weight gain associated with out of school time. Snacking also is linked with increased screen time, both are associated with overweight and obesity (3).

Carroll, Nicholas et al. (14) found that nearly 60% of mothers and 50% of fathers reported that their meal routines had changed since COVID-19; the most reported changes included spending more time cooking, making more meals from scratch, eating more meals with children, and involving children in meal preparation more often. Approximately 10% of mothers and 5% of fathers reported food security concerns either in the past month or over the next 6 months (14).

Study authors argue that identifying the impact that COVID-19 pandemic on families with young children will help inform the development of effective, family-based health promotion interventions that are relevant in this post-COVID-19 context. Researchers suggest longitudinal research is needed to understand the impact of these behavior changes and stressors on health and weight-related outcomes among families. They conclude that response plans should include a focus on ensuring adequate income, minimizing family stress, and supporting healthful eating, activity, and screen-time behaviors among all Canadian families (14).

Supplement intake: While there are no current supplement recommendations to prevent or treat COVID-19, many people took supplements hoping it may boost their immune system and we’ve seen an increase in sales of supplements marketed for immune health. We examined different reasons that may have contributed to this increase. Elderberry supplement purchases increased at twice the rate after the pandemic began. Animal research suggested that elderberry may prevent upper respiratory tract infections. (17) Some research has shown regularly consuming 200 mg/day or more of vitamin C can reduce the severity and duration of cold symptoms. (17) In individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 10 ng/mL, there has been some evidence suggesting that vitamin D supplementation assists in preventing respiratory tract infections. Some evidence indicated that zinc may help reduce the length of the common cold and severity of COVID-19 symptoms such as diarrhea and loss of taste and smell.

RESULTS

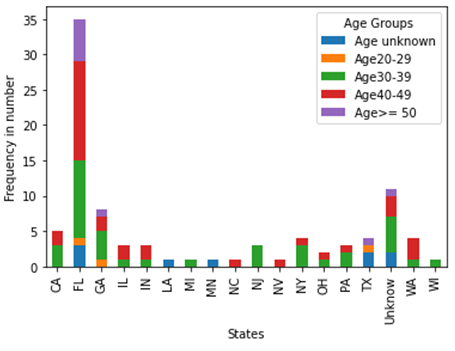

We attempted to distribute our survey to participants in all 50 states, but only participants from 17 states took part. Most of the respondents are aged between 30 – 49 (77%), are non-single (82%) and from Florida (39%) (Figure 1). We divided these respondents by their working status before the pandemic in 5 groups, as work in office full-time and part-time, work from home full-time and part-time, and stay at home. The percentages for these groups are 43%, 10%, 13%, 6%, and 28%, respectively. According to our data, 43% of the respondents stated that they worked more than 40 hours per week before the pandemic, 83% of them did not change their total working hours and 9% of them reduced their working hours during the pandemic.

In the data, 74% (67 obs.) of the families have one or two children, and 30% of families have children in middle childhood (6 – 8 years), 29% have Toddlers (between 1-3 years), and 25% have preschoolers (between 3-5 years). Among these families, 38% claimed that they have a normal diet, and 22% of them follow an Ethnic diet, which includes Chinese, Indian, Mexican, etc. Figure 2. shows the distribution of the diet types in Respondent’s ages.

There are 42% of families who claim that their children ate more food during the pandemic and 38% who claim no changes. 27% of the families did not note any identification of types of food, such as in fruits and vegetables, eating out, and meal-delivery. 47% and 23% of the families state that the children ate more snacks and sweetened drinks, respectively. 38% of them did not notice any changes in these two types of food. 54% of the families had more snacks, 38% of them did not use any supplements for their children, 54% did not change the number of their meals. 39% of the respondents considered any changes were because of the children’s development and only 13% of them thought it was because of the pandemic (see Figure 5).

Discussion of results: Based on the research papers we read, it is not clear if the different options and behaviors arising from different working status (at home or away, hours etc.) had any impact on the oral consumption and nutritional status of their children. The toddler (1-3 years) group along with middle childhood (6-8 years) are the highest reported age groups who noted that eating habits have been affected by the pandemic.

According to our findings, all four work groups tend to have a normal diet for their child(ren), 38%, 33%, 67%, and 40% for work full time in office and from home and work part time in office and home, respectively. The next choice for the first three groups (for work full time in office, from home and work part time in office) was the Ethnic diet, 21%, 17%, and 22%, while householders who stay at home prefer to have a 32% Ethnic diet and 28% normal diet. Any changes in dietary habits could possibly be related to the availability of ethnic foods at the beginning of the pandemic, as many of the ethnic stores were closed (see Figure 3).

In terms of the changes in food quantity consumed, the highest percentage was for eating more (41%) followed by no change (36%). This is consistent with the findings of Paslakis, et al (2) which is linked with an increased intake at nighttime and snacking. One-third of the families reported an increase in high-calorie snacks, sweets and almost half reportedn increase in processed foods. For those groups who work part-time from home and/or stay at home, there appears to be no change in consumption.

When comparing changes in food type consumed from the start of the pandemic through late spring to early summer of 2021 vs. before the pandemic; eating more fruit and vegetables was more likely than eating less across all working groups (23%, 17%, 11% , 20%, 28%vs. 15%, 0%, 0%, 20%, 20%) except in the case of the group working from home part time (20% vs. 20%). Ordering meal delivery kits (eg.: Sun Basket, Blue Apron, Hello Fresh) was also more likely across the same working groups (23%, 17%, 22%, 12% vs. 3%, 8%, 0%, 0%). These findings are consistent with Hammons et al. (5), where families were finding themselves cooking more and consuming more meals together as a family after the pandemic, due to being home for longer periods of the day (5). An increase in family meals helps family members to feel more connected and has been associated with many benefits such as an increase in consumption of fruits and vegetable and an improvement in diet quality overall.

Parents working from home full time or in the office full time were more likely to increase ordering out from fast food venues and restaurants (33%, 26% vs. 0%, 15%). Parents working from home part-time, in office part-time or stay at home were more likely to decrease ordering out from fast food venues and restaurants during the pandemic (67% 32% vs. 11%, 24%). Stay at home parents in our survey (which made up 27% of survey respondents by work status) were the largest group (50%) to not notice any changes in food type consumed. There were around 1/3 of other groups who also did not change their habitual food-types.

Parents from all working groups in our survey were likely to notice an increase in processed snack intake (eg.: chips, cookies, crackers, candy) among their child(ren) during the pandemic compared to before (46%, 42%, 33%, 40%, 56%). Caroll (14) and others evaluated the changes in health behaviors post-COVID-19 pandemic among a subset of middle-income Canadian families of young children, average age = 6 years, n = 310 children (14). Parents noticed changes in eating behaviors among 42% of children in households and, like our study, their results showed parents noticing their children notably eating more snacks (among 55% of children).

Other than parents belonging to the working from home part-time group, parents belonging to all work statuses noticed an increase in their child(ren)’s intake of sweetened beverages during the pandemic (28%, 25%, 11%, 0%, 24%). Parents who worked in the office part-time were the largest group to notice no change in sweetened beverage or snack intake among their children making up 67% of parents from this group.

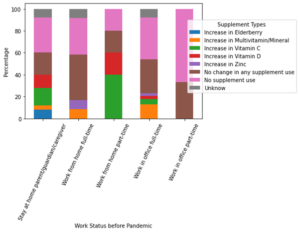

Almost all parents (other than stay at home parents) did not notice an increase in elderberry supplement intake during the pandemic. Over 50% of parents from all working groups either noticed no change, or reported no supplement intake during the pandemic, except for parents working-from-home part time. All parents working in the office part-time in our study (n=9) did not notice an increase in elderberry, vitamin D, vitamin C, zinc or MVT supplement intake, they either did not notice the changes (33%) or did not take the supplements (67%). Figure 4 shows the percentages over these working groups. Though there are no current supplement recommendations to prevent or treat COVID-19, we expected to see an increase in these supplements among children of parents from all working statuses, due to the recent increase in sales of supplements marketed for immune health in recent years (17). Our findings may be explained by the often-added cost these supplements bring. Future research should include economic data about participating households, which often drives purchasing decisions.

Overall, our results show that most households did not give their child(ren) supplements (especially for households who work in office part-time, 67% of them says no supplements) and among those that did, there were no changes (31%, 42%, 33% 20%, and 20%, for households work in office full-time, from home full-time, work in office part-time, from home part-time, and stay at home, respectively). While supplement sales did increase since the start of the pandemic, this may be associated with adult supplement use. Our results did indicate some increase in the use of Vitamin D and Vitamin C among those families with a parent/guardian /caregiver working from home part-time (20%, 40% for VD and VC, respectively) and staying at home (12% and 16% for VD and VC, respectively). Over 50% of the households did not report a change in their meals consumed throughout the day, especially for the people who work from home part-time (80%). This was surprising as based on our initial research, we expected an increase in meals consumed. It would be beneficial to further examine whether households were experiencing food insecurity.

Of those households that observed changes in their child(ren), 40% felt it was due to their child(ren)’s development and 13% of all households thought the changes were due to the Pandemic (Figure 5).

Limitations: With the small sample size, there are some limitations for this research. For example, we have been unable to cover all the US states and some of the working groups only have very limited samples.

CONCLUSION

There are things we need to consider in order to protect children’s food security in circumstances similar to the pandemic. To address the issue of food insecurity, there is a need to correct the economic crisis that has exacerbated job inequality. Basic income protection during times of crisis ensures the security of all and lessens the risk of eating pathology and developmental concerns arising as a result of food insecurity. Food security is a factor that influences dignity, justice, life, and development (2). Our suggestion is that farmer’s markets and ethnic food stores should consider delivery as part of essential food services and develop social distancing protocols for these markets.

Figure 1. Demographic Information from Respondents

Figure 2. Diet Types in Respondent’s Ages

Figure 3. The type of diets aligned with work status before the pandemic

Figure 4 Supplement Changes vs. Work Status before the Pandemic

Figure 5. Reasons for Changes vs. Work Status before Pandemic

REFERENCES:

- López-Bueno, R., López-Sánchez, G. F., Casajús, J. A., Calatayud, J., Tully, M. A., & Smith, L. Potential health-related behaviors for pre-school and school-aged children During COVID-19 Lockdown: A Narrative Review. Preventive Medicine. 2021; 143: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106349

- Paslakis, G., Dimitropoulos, G., Katzman, D.K., A call to action to address COVID-19–induced global food insecurity to prevent hunger, malnutrition, and eating pathology, Nutrition Reviews, 2021; 79 (1):114–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa069

- Rundle, A. G., Park, Y., Herbstman, J. B., Kinsey, E. W., & Wang, Y. C. COVID‐19 Related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity, 2020; 28 (6):1008–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22813

- Jiao, W. Y., Wang, L. N., Liu, J., Fang, S. F., Jiao, F. Y., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., & Somekh, E. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the covid-19 epidemic. Pediatric Pharmacology. 2020;17 (3):230–233. https://doi.org/10.15690/pf.v17i3.2127

- Hammons, A. J., & Robart, R. Family food environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Children. 2021; 8 (5): 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8050354

- Krukowski, R. A., Jagsi, R., & Cardel, M. I. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Women’s Health. 2021; 30 (3):341–347. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8710

- Di Renzo, L., Gualtieri, P., Pivari, F., Soldati, L, Attinà, A., Cinelli, G., Leggeri, C., Caparello, G., Barrea, L., Scerbo, F., Esposito, E., & De Lorenzo, A. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 2020; 18: 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5

- Bauer L. The COVID-19 crisis has already left too many children hungry in America.

- Morales, D.X., Morales, S.A. & Beltran, T.F. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Household Food Insecurity During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Study. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2021; 8:1300–1314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00892-7

- Patrick, S.W. Henkhaus, L.E., Zickafoose, J.S., Alese, K.L.Halvorson, Loch, S., Letterie, M., & Davis, M.M. “Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey.” Pediatrics. 2020; 146 (4):e2020016824; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-016824

- Loth, K. A., Ji, Z., Wolfson, J., Berge, J. M., Neumark-Sztainer, D. & Fisher, J. O. COVID-19 pandemic shifts in food-related parenting practices within an ethnically/racially and socioeconomically diverse sample of families of preschool-aged children. Appetite; 2022; 168:105714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105714

- Adams, E. L., Caccavale, L. J., Smith, D., and Bean, M. K. Food insecurity, the home food environment, and parent feeding practices in the era of Covid‐19. Obesity, 2020; 28 (11):2056–2063. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22996

- Philippe, K., Chabanet, C., Issanchou, S. & Monnery-Patris, S. (2021). Child eating behaviors, parental feeding practices and food shopping motivations during the COVID-19 lockdown in France: (How) did they change?. Appetite, 2021;161: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105132

- Carroll, N., Sadowski, A., Laila, A., Hruska, V., Nixon, M., Ma, D.W.L., & Haines, J. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients. 2020;12 (8):2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352

- Ivor, B., Griggs, R.C., Wing, E.J., and Fitz, J.G. Andreoli and Carpenter’s Cecil Essentials of Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders Publishers. 2010.

- Iddir, M., Brito, A., Dingeo, G., Fernandez Del Campo, SS., Samouda, H., La Frano, MR., Bohn T. Strengthening the Immune System and Reducing Inflammation and Oxidative Stress through Diet and Nutrition: Considerations during the COVID-19 Crisis. Nutrients. 2020; 12(6):1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061562

- S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Office of dietary supplements – dietary supplements in the time of covid-19. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/COVID19-HealthProfessional/ Accessed November 13, 2021

© Copyright 2023, All Rights Reserved. Use of this content signifies your agreement to the T&Cs of Unified Citation Journals

This abstract of Manuscript/Paper/Article is an open access Manuscript/Paper/Article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which allows and permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and accepted.

This communication and any documents, or files, attached to it, constitute an electronic communication within the scope of the Electronic Communication Privacy Act (https://it.ojp.gov/PrivacyLiberty/authorities/statutes/1285)

To citation of this article: Najla Al Nassar-Moyles, DHSc, MS, RDN Shirley Matenda, MS, CD, RDN, CDCES, Sarah Thomas-Anderson, MS, RDN, CCRP, Child Nutrition During the Pandemic: The Impact of Work-Status, Unified Nursing Research, Midwifery & Women’s Health Journal